INTRODUCTION

IT IS CURIOUS TO NOTE that with all the growth of enthusiasm in Martial Arts, there is relatively little knowledge of the Chinese self-defense cultural arts. These arts have flourished for thousands of years. The Chinese have traditionally seemed reluctant to disclose their skills to people outside of China. The arts are practiced for health and self-defense and their practitioners are many. In fact, according to Dr. William C. Hu, a Martial Arts historian, “Tai Chi Ch’uan,” one of many “Gung Fu” systems, is by far the most widely practiced system of self-defense in the world: He says, “Karate practitioners number a total of perhaps five or six million in all countries; whereas, hundreds of millions of people engage in this Chinese art” There are more than three hundred systems of “Gung-fu” in China. Each system has such value and depth that it would take more than one book to talk about any one system. The knowledge within “Gung-Fu” is astounding; we can only speak in generalities. Perhaps most interesting is the philosophy that is entwined into each “Gung-fu” art. One actually lives “Gung-fu” … one does not just practice it. Movements become graceful, expressive and beautiful; yet behind this look of eloquence lies power and devastation hard to imagine. Many systems emphasize tremendous strength, externally and internally. Yet others will emphasize one to become like water; yielding, flowing, surrounding and soft. In attempting to break down the many “Gung-fu” systems, we have divided the arts of the Northern part of China from those of the South. If a man studies in the North, his art is chiefly use of his legs. If he studies in the South, he is strong in the hand arts. The differences are inexhaustible. A “Gung-fu” man does not hit his opponent outright. He strikes precisely, cunningly and thoroughly. He knows what he hits, how it will affect his opponent and he knows how to cure him. We are dealing with such a “many faceted” art whose beauty is abundant, whose history is deep, and whose followers are many. It is mysterious and yet its physics follow Newton’s Laws: It is ballet like, yet enables its practitioners to kill, maim or control an opponent. It is art developed by a cultural people, and yet it often fashions itself after animals. “Gung-Fu” is like the rose … beautiful, alluring, yet sharp and painful. So, too, must the reader approach these arts. If grasped too quickly and not carefully, the arts will prove meaningless … their beauty and naturalness hidden. A beginning student is said to start out in a dark room while the master stands in the sunlight. Let this book open the first door.

FOREWORD

As long ago as 2,500 years, the Chinese sage Confucius was asked, “Great teacher, tell us about the life after death.” Confucius replied, “We have not yet learned to know life, how can we know death?” Upon the vast sea of human life the Chinese seem to ride a strange ship. Contrary to Western philosophical belief, they don’t quite see themselves as masters of the natural world, nor do they envision man as the prime object of nature’s creation. This ecological approach tends to draw man in tune with the natural forces. A Chinese does not conquer a mountain … he befriends it. Man becomes a link, a vital one, in a fluctuating chain of natural events. Man, Heaven and Earth form but a single balanced unity. The desire is for an eternal harmony. Reverence for the natural order underlies both Confucian and Taoist philosophy. Chinese civilization and art would have been utterly different if a man by the name of Lao Tzu had never existed. Even Confucianism, the dominant system in Chinese history and thought, would not have been the same. No one can really hope to understand the physical arts of China without a thorough appreciation of the profound philosophy of Lao Tzu or Confucius. It is true that while Confucianism emphasizes social order and an active life, Taoism expresses an almost opposing view. Taoism concentrates on tranquility and individual life. However, in opposing Confucian conformity with nonconformity, Taoism is Confucianism’s severe critic. This is the subtle mixing of opposing forces which creates the “Grand Terminus,” the whole. When we come to Chinese civilization and its physical arts, the general impression is that it is human, rationalistic, and easily understandable. The Chinese mind, on the whole, is humanistic and philosophically oriented. However, in close viewing of Chinese arts, one is struck by the vast differences from the West; both in approach, values and objectives within. The sea of human life forever laps upon the shores of Chinese thought as the Western logician’s assumptions of, “I am all right, you are all wrong,” are not part of Chinese thinking. It strikes the Western tourist as curious that the Chinese have no sense of accuracy, particularly of facts and figures The difference is in approach. I ask the reader to keep this in mind as he looks upon these highly valued Chinese arts. In studying Chinese physical self-defense arts we will have to dive deeply into the precepts of Taoism and Confucianism. For it is with these philosophies that these arts were horn and it is within these philosophies that these arts flourish. The reader must understand that we must approach these cultural arts as precisely that … arts. We are going to have to forget the Western ideas about sports, sportsmanship, contest and honor for a while. The philosophy of these arts differs from Western ideas as drastically as some of the strange, beautiful movements you will see. Many of the basic values within “Gung Fu” will appear in direct opposition to Western activities of the same nature. What you will read about is indeed an art. Like all arts, one must bring a certain kind of understanding, a tolerance with them if true knowledge is to be gained. For, “When the people of the world all know beauty as beauty, there arises the recognition of ugliness. Then they all know the good as good.” (Ch. II)

YIN AND YANG

The foundation to all Chinese cultural arts and philosophy is the correlation of the two basic forces in the cosmos; Yin and Yang. Desire for harmony with nature stems from ancient unknown philosophers who devised a cosmology and philosophical interpretation of that natural order. In writings of Chinese ideas of the Fourth Century, there appears the existence of two interacting forces, the Yin and the Yang in all actions, and displays of nature, including man. Each represents a collection of qualities. Yang is the positive, bright, active force. Everything that is active, warm, dry, hard, steady and masculine is said to have qualities of Yang. Yin is the negative, dark, inactive force. Its connotations are everything passive, cold, wet, soft, dark, mysterious, changeable and feminine. The contraries are as inexhaustible as its philosophical expressions. Symbolically, these two forces are entwined in a circle, the whole which the Chinese would call the “Grand Terminus” or “Great Ultimate.” Most interesting in this philosophical study is that never are these contraries ever in direct opposition to each other. The conception of Yin and Yang dines not hold for direct dualism i.e., light and dark or good and evil.

Tones of Yin and Yang are basically in tune with each other. Each corollary compliments each other, each is necessary to form the whole, to complete the order. Lao Tzu said, “Being and non-being produce each other; difficult and easy complete each other; long and short contrast each other; high and low distinguish each other; sound and voice harmonize each other.” (Ch. 2). The Yang concept is usually depicted by a sphere or “double fish” symbol. The opposing force blends in a circular pattern, each balanced exactly. In the very heart of the Yin side is a small part of the Yang and thus part of Yin is with the Yang. You will notice that one is always placed in the very heart of the other. Within the most Yang of forces there is always Yin. In the most outer of a violent storm there is always a peaceful calm. In the innermost part of Yin, there is Yang. In the center of a small, sleeping rabbit there is a fast beating heart. It is perhaps easy to understand how such a simple blend of corollaries could become a way of life. Man no longer stands as opposite to nature; rather, using the Yin and Yang philosophy, man blends with nature and finds that his inner-most soul is like the storms, the mountains, the very nature which surrounds him. In “Gung Fu” there are many systems which employ very hard, strong moves. There are systems which, in turn, make use of soft, quick moves. It is all “Gung Fu” … all martial art. As the subtle opposites of Yin and Yang blend, so do the soft and hard systems blend to a unity. What appears hard is done with ease, what appears soft is deadly. A “Gung Fu” artist makes use of his opponent’s weakness, which always exists. In the strongest of men there is always a weak point. And curiously enough, that weakness can most readily be found at the center of strength . For example, if a man delivers a punch, in doing so he must extend his arm, raise his elbow and create an opening. “Gung, Fu” is not learning how to overcome your opponent, it is learning to find the Yin within his Yang, the weakness within his strength. The blending of the Yin and Yang form a circular pattern. Unlike many martial arts, the Chinese make much use of the circle in the softness or firmness of their attacks for neutralizing or dissipating attacks. A direct attack is usu ally in a straight line. If one force directly meets another direct force, the weaker will suffer injury. Use of circular patterns can be used to let the force coining in overexert and it can be redirected. This strong force (Yang) can be neutralized if the weaker force (Yin) blends in a circular pattern. Of course, I speak in very general terms about “Gung Fu;” not all moves are circular, nor do all neutralize. The correlating idea of the “Gung Fu” arts to the Yin/Yang concept is inexhaustible. In fact, it is such a foundation for so many arts that the Yin/Yang symbol is often used within an association or system as an emblem or identification mark. The philosophical connotations and implication of the Yin/Yang could warrant a book in itself. It is but one basic Chinese precept which underlies these cultural arts.

WU WEI

One Chinese concept which is perhaps most foreign to Western thinking is that of “wu-wei.” The positive forces within nature are said to have no name, and conversely, its activity is characterized by taking no action. If a man follows “wu-wei” he takes no action. However, taking no action does not mean to do absolutely nothing. Rather, it means to take no overt or artificial action. It is sort of a “creative quietude,” to be calm and reserved, to let the forces of nature pass through one naturally. Action invariably leads to reaction. Reaction is an undesired trait if it proves unfavorable for the artist. The TAO TE CHING ex-pressed this concept: “Stretch a bow to the very fullest, and you will wish you had stopped in time. Temper a sword-edge to its very sharpest, and the edge will not last long. When gold and jade fill your hall, you will not be able to keep them safe. To be proud with wealth and honor is to sow the seeds of one’s own downfall. Retire when your work is done; such is Heaven’s way (Ch. 9). To act just enough is not part of the Western standard for work. And yet, the Chinese invariably grow and live by such a doctrine. Such is true with their arts. In “Gung Fu” there is a “shedding off” of excess movements. Many systems emphasize concise, short moves. Many systems use lone, extended movement. However, in all systems, no human movement is wasted. A good artist acts just enough in accordance to the situation. To overact is to overcommit. It is precisely this kind of overaction that the “Gung Fu” artist will try to bring out in his opponent. To extend one’s forces is to extend one’s protection, one’s balance and one’s susceptibility to counter. A “Gung Fu” man knows his opponent is weakest when he attacks: The paradoxical expression of “wu-wei” is the key to Chinese mysticism. Its true meaning is hard to translate. It is the way of the sage, the way of the artist. It is a key to understanding “Gang Fu” movement. “A well-shut door needs no bolts, and yet it cannot be opened.” (Ch. 27).

CHI

In both Taoism and Confucianism there is a concentration of vital life force … breath. It is interesting that Taoism wants this force to be weak, whereas Confucianism wants the vital force to be strong. Although this vital life force has many names, we would generally say it usually represented by the word “chi.” It has often been loosely described as “intrinsic energy.” Intrinsic energy is strength from within … beyond the muscular movement. It is both developed and used. Robert W. Smith says of “chi:” “To master this energy is to pierce the unknown and to reach the state where life and death lose their qualities of fear. When you achieve this a threat does not disturb nor a temptation caress. You become true master of your self.” (SECRETS OF SHAOLIN TEMPLE BOXING) “Chi” can be related as a single point: a single point of mind, a single point of the physical. True “chi” is the combination of mind and physical to one single point. It is often described as super-human strength or that of animals. Often, “Gung Fu” systems employ the physical enactments of animals. When needed, the human body secretes adrenalin. “Chi” might be said to be control of the adrenalin flow to a specific point. Thus, one can produce the strength he does not have, but does have. “Chi” is the finer point of concentration, the undiscovered you. It comes naturally if developed correctly. When you seek it, you pass it. When it becomes you, you know it. The strength within you can be compared to the sun. If one takes a magnifying glass, one can magnify the heat of the sun to a small point. If one uses “chi”, he can magnify his strength to a single small point as well. It is a natural force and must be developed naturally. It is a basic tool of the “Gung Fu” man. He develops it and uses it to its best advantage. Again, it is only use of a natural force whose power reaches far. It would be far too simple to say that “Gang Fu” “builds” character. Long ago, Confucius laid much emphasis on the inner character of man. “Jen” or human heartedness is the spirit of an individual which won’t vary. Through the hard works of “Gung Fu” one can build a dependable inner spirit which won’t change. He builds in physical force to make a moral one. Confucius believed that true peace starts in the individual. “Wen,” as the arts of peace were called, were designed to develop the individual man. Thus, paradoxically, the arts of fighting are within the arts of peace. In “Gang Fu” the peace is within the man. We will see that the “Gang Fu” depth of teaching and development is as broad as life itself. For it becomes a way of life, as well as a way of death.

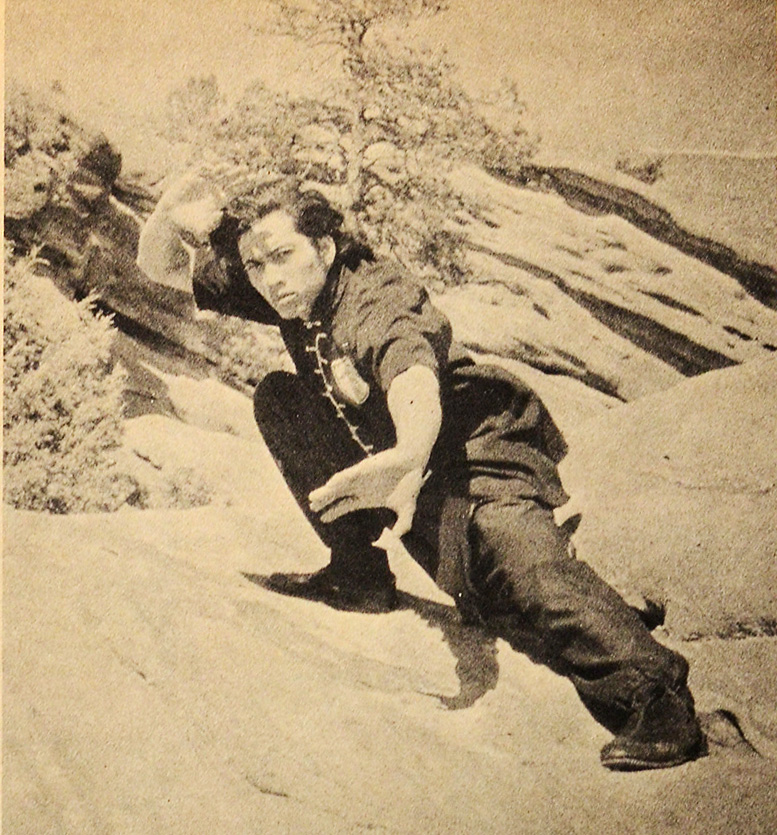

Al Dacascos began his training in the martial arts almost 20 years ago in Hawaii under Master Adriatic. Emporado. Al came to the U.S. mainland and began spreading his art on the West Coast. He later became one of the first Kung-Fu practitioners to enter tournament competition and has since then won over 200 trophies in Kato and free sparring events throughout the United States. At a recent St. Louis tournament, an area where real Kung-Fu was never really seen but frequently joked about in Karate circles due to misrepresentation of the art in the past, Mr. Dacascos brought 5,000 people to their feet in an awesome standing ovation for his 30 minute demonstration. Through action and not chatter, Mr. Dacascos brought respect and interest in Kung Fu to the Midwest. Mr. Dacascos and his wife Malia, one of America’s top female competitors, now teach Kung Fu at their schools in Denver, Colorado.

The entire book, “The Story of Kong. Fu,” will be featured in this magazine. The following text will be continued in the coming editions of PROFESSIONAL KARATE so our readers and students of Kung-Fu can accumulate more knowledge of this ancient Chinese art.